In this post, we’re going to take a fun look at the quirky origins of animal names and how different animals are seen in unique ways, which gives them their special names.

Armadillo

🎉 QUIZ TIME, FRIENDS! 🎉

🔍 Thinking Time 🔍

What do these four fabulous words have in common: Tortilla, Vanilla, Quesadilla, and Armadillo?⏳ Tick… tock… tick… tock… ⏳

🎊 Ding ding ding! Got it?🎊

Here comes the reveal…📣 They all end with a spicy twist — “-illa” or “-illo”! Spanish words! See also the map of armadillo in Spanish with all the varieties.

Let’s strip off the armor!

When the first European sailors arrived in South America, they encountered a curious little creature covered in bony plates. They named it armadillo, which literally means “little armored one” — a diminutive of the Spanish word armado “armored”. It’s a linguistic cousin to English words like arm, armor, and even armada.

Meanwhile, other languages created calques — literal translations that capture the meaning rather than the sound. In Polish, for example, the armadillo is called pancernik, a diminutive of pancerz “armor”.

Back to the jungle

However, long before the Europeans showed up, indigenous peoples of South America had their own names. In Guaraní, the armadillo was called tatu — a word later borrowed into Spanish, French, and even Hungarian!

Notch on your belt

Take a look at the armadillo’s body and you’ll notice it’s wrapped in banded plates — almost like it’s wearing a belt! Some languages highlight this unique feature: Czech: pásovec (from pás – belt), German: Gürteltier (literally “belt animal”), or Estonian: vöölane (from vöö – belt)

Cat

“Cat” is a word with a remarkably uniform spread across many languages. Terms such as Ukrainian kit (кіт) or Estonian kass appear to derive from the same root as the English word, though the exact origin of this root remains uncertain. It was likely Afro-Asiatic in origin, as suggested by parallels such as Nubian kadis.

There are, however, two notable exceptions. In the Balkans, many languages use forms derived from maca, probably an onomatopoetic development—similar to Romanian pisică or Finnish kissa, which also seem imitative or independent. Farther east, in West and Central Asia, we encounter another distinct lineage in the Turkic root pišik.

See also fictional cat characters like Scratchy from the Simpsons.

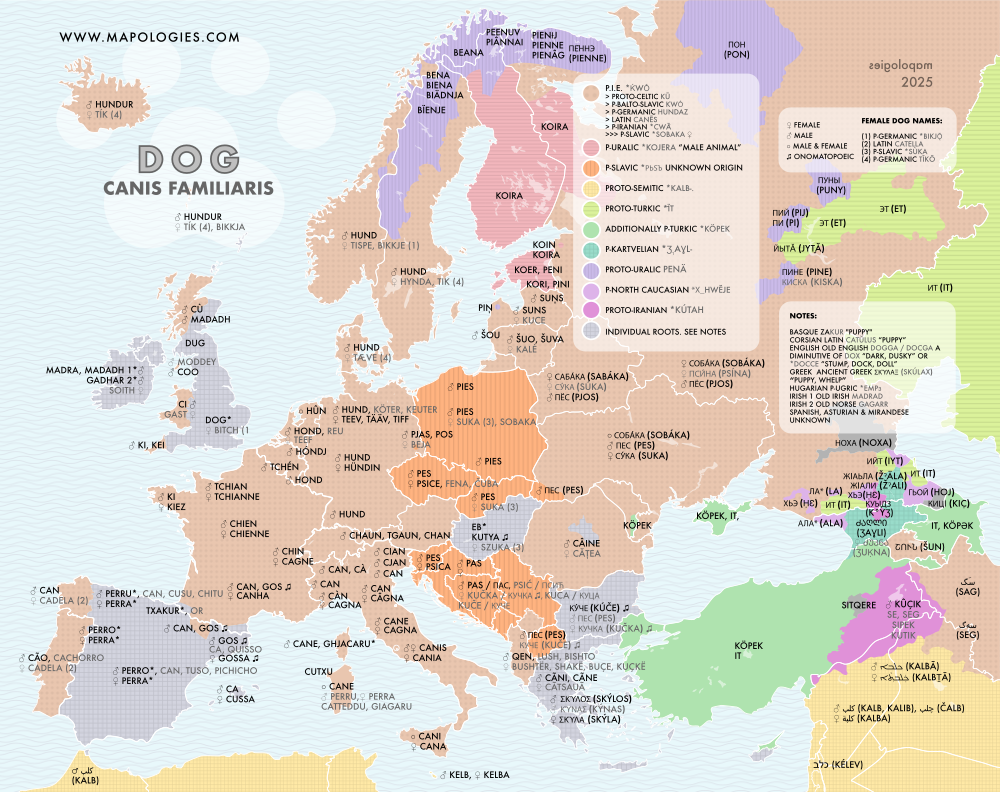

Dog

Breeds of Words

Despite their shared origins, dogs could hardly be more different from wolves. In much the same way, most European languages trace back to a common Proto-Indo-European root, ḱwṓ, and an even earlier form, ḱwón-s. Over millennia, the words derived from this ancestor have taken on remarkably diverse forms: Portuguese cão, Danish hund, and Persian sag, among others, even Russian sobaka (“bitch”). This diversity is comparable to the wide variety of dog breeds themselves.

See also fictional dog characters like Goofy or Dogmatix. Did you know there’s an interesting connection between the @ symbol and dogs? Find it out!

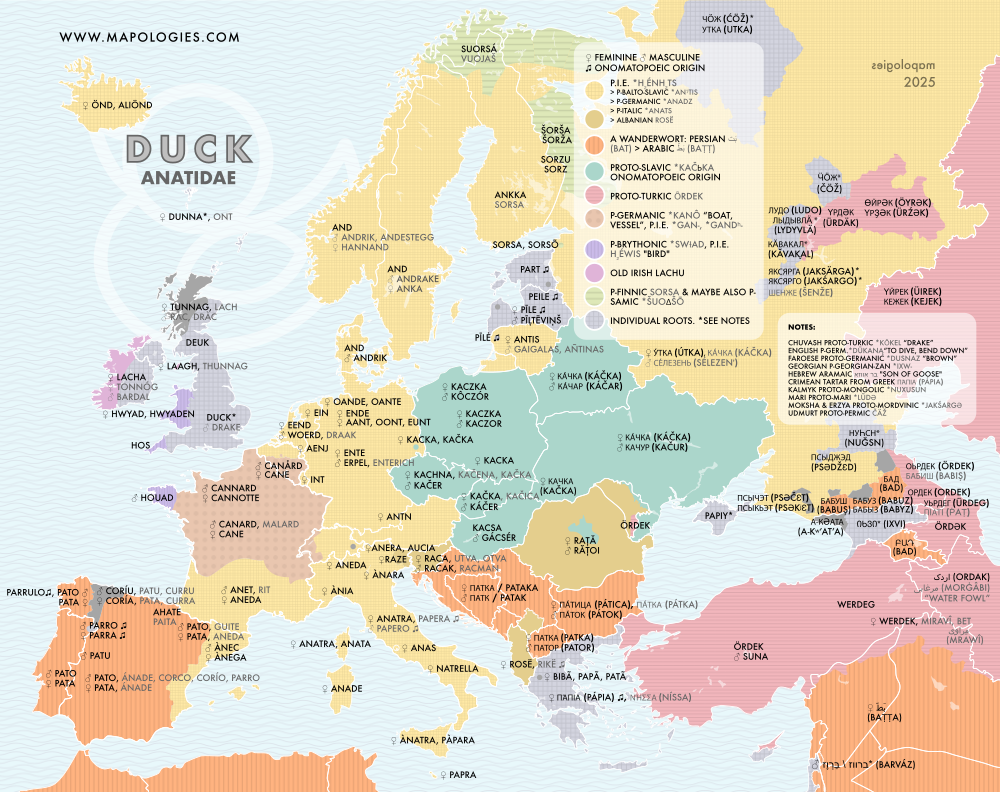

Duck

“What am I seeing here? is it a boat or a duck?”

This situation must have been fairly common in the past, since the etymological origin of the French word for “duck” (canard or cane) comes from a Proto-Germanic term meaning boat or vessel.

However, this kind of semantic shift is very unusual among other languages. Most languages still use words derived from the ancient Proto-Indo-European root: *h₂énh₂t. We find this root spread throughout the West—from the Catalan ànec & ànega in the south, all the way to Icelandic önd in the north—and also in the East as far as Russian утка (utka) in Cyrillic.

Around the Mediterranean, another word for “duck” is also widespread. Its origin may be the Persian bat (بط), but this is uncertain. Variants of it appear in Galician pato & pata, Arabic baṭṭa (بطّة), and Bulgarian патѝца (patitsa) & паток (patok).

Many Slavic languages retain their own inherited word, such as Belarusian качка (kačka) and Slovak kačka. Hungarian kacsa was probably borrowed from one of these. All of these forms ultimately come from an onomatopoetic Proto-Slavic word kačьka (качка).

See also fictional duck characters like Donald Duck and the rest of his family.

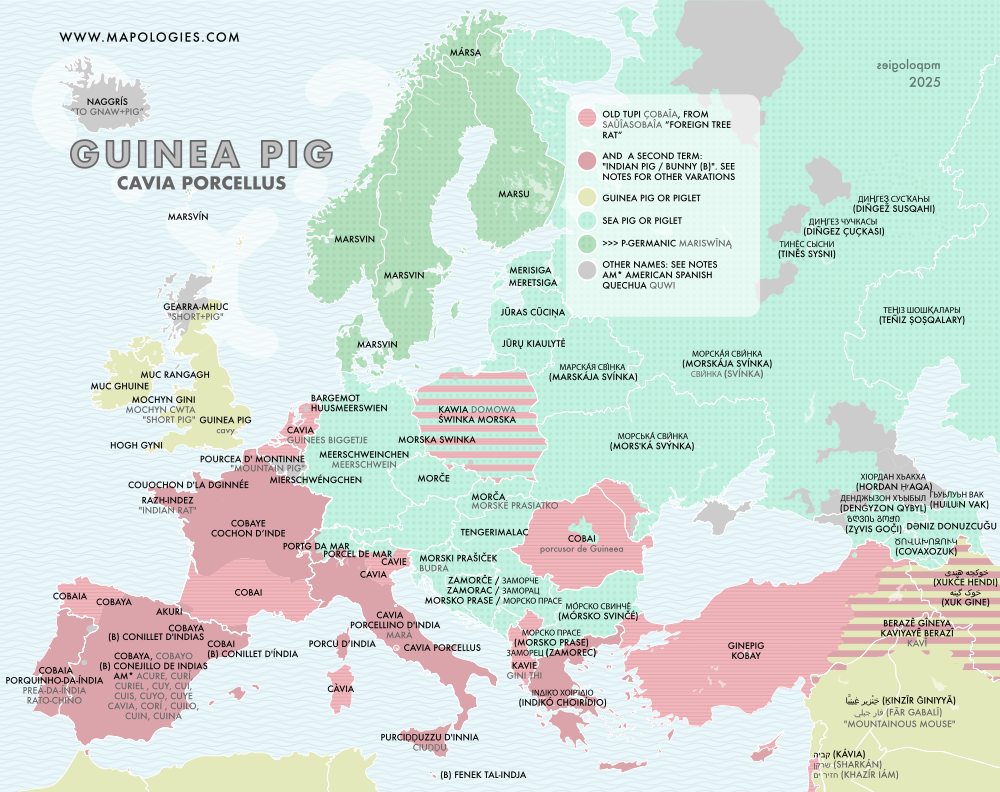

Guinea pig

Despite these connections, none of these terms derive directly from Latin or Proto-Italic roots. Instead, they appear to have been borrowed from an unknown language or languages, likely originating from the Iberian Peninsula, though much about this source remains a mystery.

Guinea or India pig?

In English, the term “Guinea“ was commonly used to describe far-off or exotic places, not specifically the West African country of the same name. Another possibility is that “Guinea” in this context is a corruption of “Guiana”, a region in northern South America—which aligns more closely with the guinea pig’s true native range. Interestingly, some languages associate the animal not with Guinea or South America, but with India. For example, in French it is called cochon d’Inde (“pig of India”), and in Greek ινδικό χοιρίδιο (indikó choirídio), meaning “little Indian pig”.

Sea Pigs

Because guinea pigs were brought to Europe by sea, many languages reflect that with names meaning “sea pig”: In German, the animal is called Meerschweinchen—literally “little sea pig.” In some Nordic tongues, it’s marsvin, a term that come from Proto-Germanic mariswīnō (from mari- meaning “sea” and swīn- meaning “pig”).

Rabbits or Pigs?

But why the association with a pig? This is likely due to the guinea pig’s plump, rounded body and its high-pitched squeals, which resemble those of a young piglet. However, not all languages make this comparison. In some, the guinea pig is likened instead to a rabbit. For instance, in Spanish, it is called conejillo de Indias (“little rabbit of the Indies”), while in Maltese, the name fenek tal-Indja translates as “Indian rabbit.”

What were they originally called?

Guinea pigs are native to the Andes, where they were domesticated thousands of years before European explorers arrived. The names used in this region reflect deep-rooted Indigenous traditions. In Quechua, they are known as quwi or jaca. With the arrival of the Spanish in South America, the term cuy or cuyo became widespread, especially in Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, where the animals remain an important part of local cuisine and culture.

In many Romance languages, the words cobaya (Spanish), cobaye (French), and cobaia (Portuguese) are commonly used. These terms likely originate from a word in Tupi, an Indigenous language of the Amazon, reflecting early colonial contact and linguistic borrowing during the European exploration of South America.

Hedgehog

Although pigs and hedgehogs are biologically distinct animals, many languages, including English, perceive a curious linguistic connection between them. This most common linguistic root traces back to the ancient Proto-Indo-European language, which underlies vocabulary across most Slavic, Germanic, and Baltic languages, and even extends as far as Ossetian and Armenian. In contrast, Romance languages developed their own separate etymological roots for these animals, as did the Turkic language family.

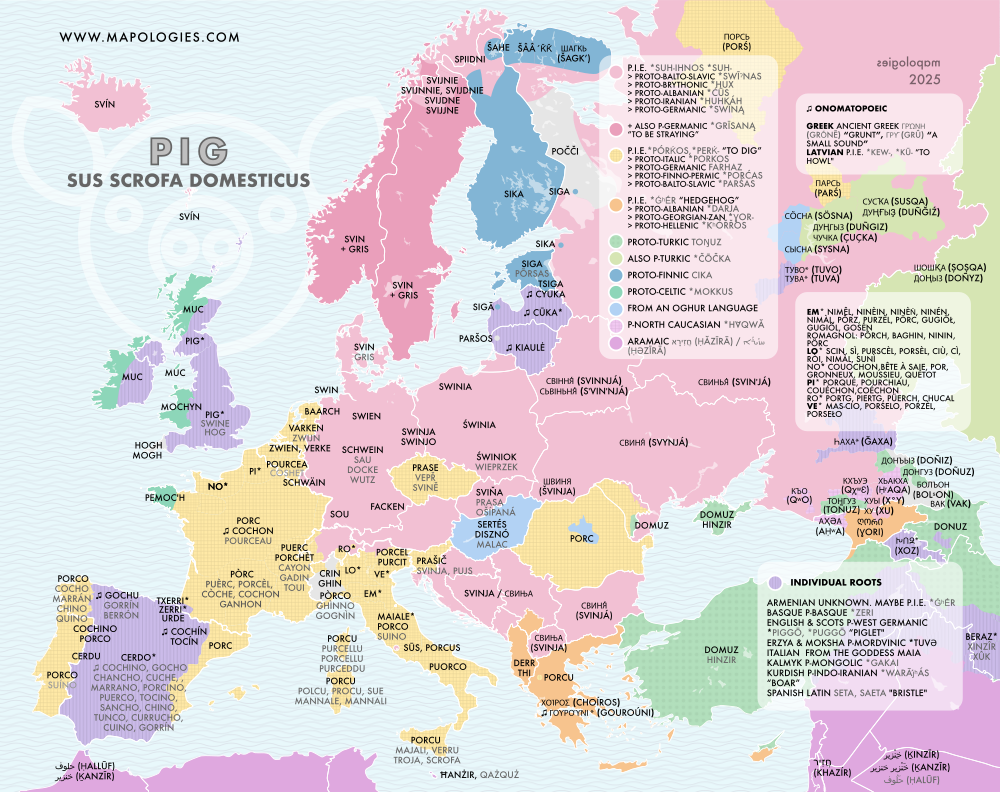

Pig

Meat & trufles

In English, the meat of the pig is called pork. Interestingly, not all languages make a distinction between the animal and its meat. It is particularly fascinating that pork has close relatives in other languages, such as French and Catalan porc, and Italian and Portuguese porco, all of which come from Latin porcus. There are also more distant relatives, like Czech prase or even Udmurt pars. The origin of these words goes back to the Proto-Indo-European root porkos, meaning “pig” and “digger” which itself comes from the verb perk — “to dig.” This makes sense, since pigs naturally use their snouts to dig up roots and insects, and thanks to their excellent sense of smell, they are even used to find truffles.

See also more information about the word “pig” in Spanish, in our section El Atlas

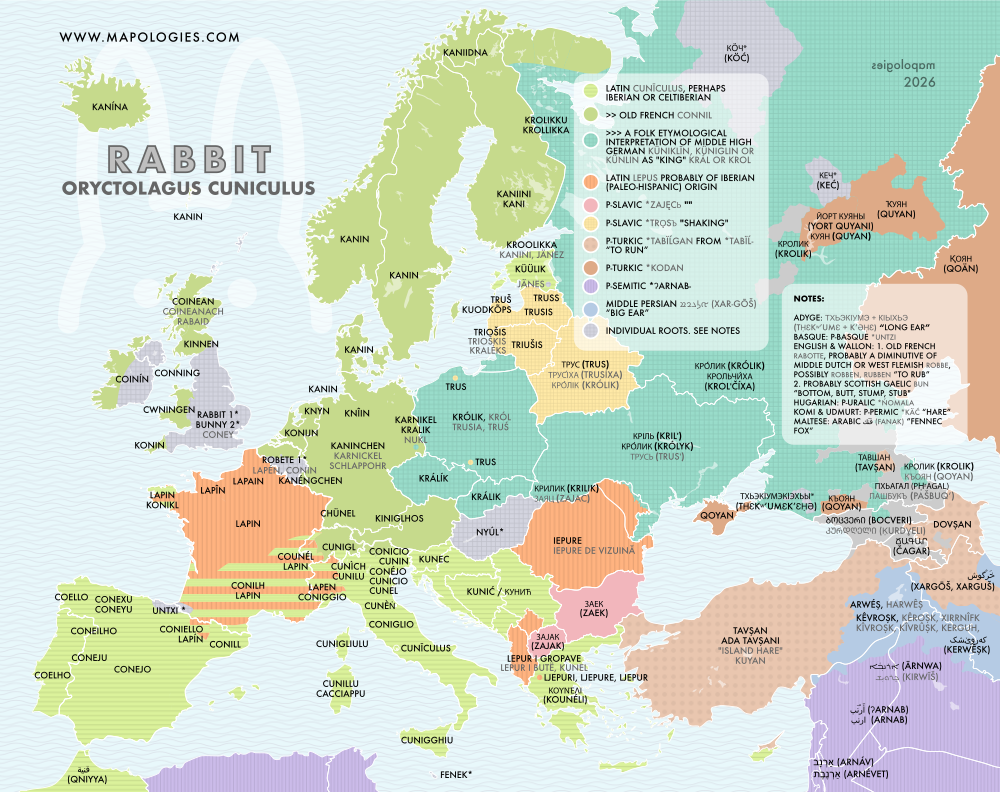

Rabbit

The etymology of the word “rabbit” is quite intriguing. It can be traced to dialectal Old French rabotte, which is likely a diminutive of Middle Dutch or West Flemish robbe. Beyond this point, the origins become speculative, potentially linking to the verb robben or rubben, meaning “to rub.”

In the rest of Europe, the term for “rabbit” originates from two Latin words: lepus (which has evolved into the French lapin or Romanian iepure) and cuniculus, from which we find descendants in Galician coello and Italian coniglio. It also extends to non-Romance languages as well, including the Serbian кунић or kunic and even the more distant Nordic languages, such as Norwegian kanin and Finnish kaniini.

Wolf

Danger

The genus Canis encompasses a wide range of animals, from humans’ best friend—the domestic dog—to one of the most dangerous enemies in the wild, the wolf. For prehistoric humans, the wolf was such a powerful and threatening presence that it was named in Proto-Indo-European as wĺ̥kʷos, possibly derived from an adjective with the meaning “dangerous.” Descendants of this root appear in nearly all Indo-European languages.

Taboo

The fear associated with the wolf was so strong among ancient hunters that even mentioning its name was believed to bring danger. As a result, in several languages the original term became taboo and was replaced by euphemistic expressions. A well-known example can be found among the Germanic peoples: while Proto-Germanic wulfaz survived in languages such as English (wolf), in Old Norse the euphemistic term vargr (“destroyer, criminal”) came to be used instead, eventually replacing ulv.

A comparable development can be observed among Turkic peoples. The Old Turkic word bȫrü originally meant “wolf.” We still find in such in Kazakh (бөрі, börı), in Bashkir and in Tatar (бүре, büre). In Turkish, however, this original term was replaced by kurt, which originally referred to a much less threatening creature, namely a fruit worm.

Howler

Another surprising phenomenon is that geographically distant languages such as Georgian and Armenian, as well as Irish and Scottish Gaelic, share a Proto-Indo-European root waylos “howler”, derived from wáy, an onomatopoeic base associated with shouting or calling. This is particularly striking because its meaning appears relatively positive compared to the strongly negative connotations of wĺ̥kʷos.