The edible grains or seeds from certain types of grasses, which are rich in carbohydrates and provide essential nutrients like fiber, vitamins, and minerals, are what we call cereals. This category includes barley, corn (maize), millet, oats, rice, rye, and wheat.

The word is a Latin term, Cerealis, meaning “relating to the Roman goddess of agriculture, Ceres“. She was named after her primary function, which was to encourage plants to grow, in Latin crēscō.

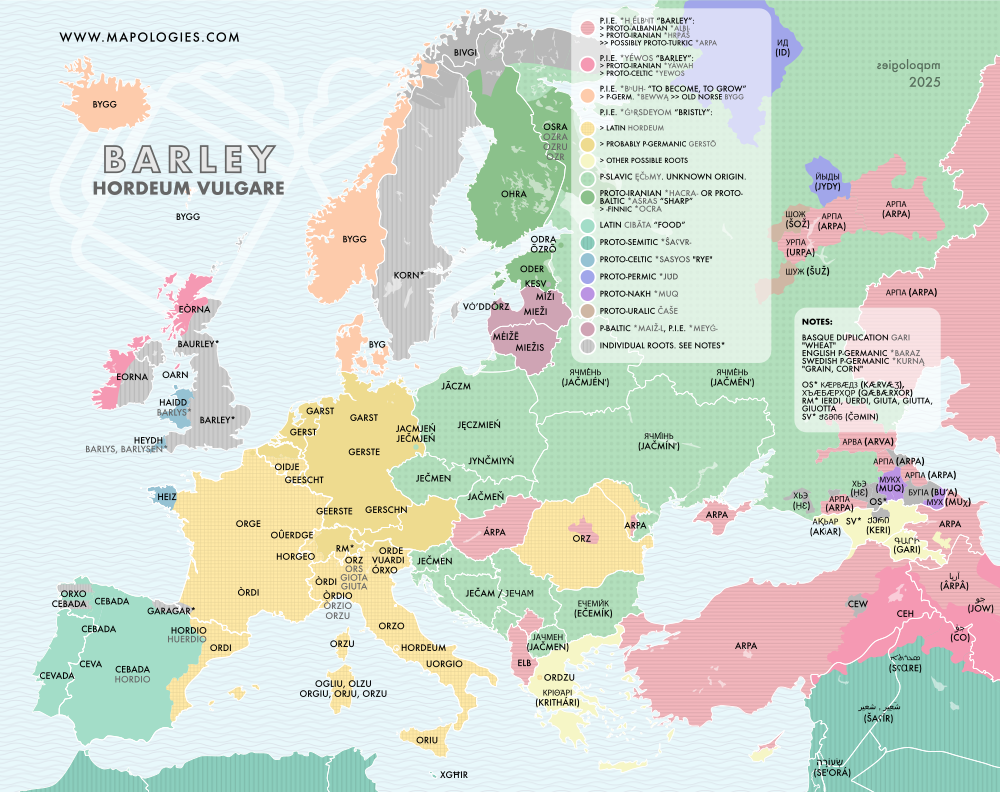

Barley, the brewer’s

Barely has one of the richest varieties of etymological roots, with more than seventeen, some of which are related. The map will represent several roots, but not many are actually dominant. Because of the ancient origins of these cereals, certain details remain obscured in history. For example, it is still uncertain whether the Finnish word ohra derives from a Baltic source or from an Iranian one.

The Latin hordĕum and its descendants in certain Romance languages (such as Italian orzo) may be related to the Germanic terms (e.g., German Gerste). Both word families trace back to the same Proto-Indo-European root ǵʰr̥sdeyom, meaning “bristly,” in reference to the long, prickly awns of the grain’s ear.

However, as mentioned earlier, not all Germanic or Romance languages preserved this term. Portuguese cevada derives from Latin cīvāta, meaning “food.” Similarly, Danish byg does not descend from that root but instead from a different one—the Proto-Indo-European bʰuH- (“to become, to grow”).

Another far-reaching connection appears in Irish eorna and Kurdish ceh, which, surprisingly, both derive from the Proto-Indo-European barley, yéwos.

Corn, the Mexican

Europe is divided in this issue: West zone where maize is called Maiz and East zone, Kukuruz. Both terms have fascinating and diverse etymologies.

Zea mays, maize, or corn was first domesticated in Mexico around 9,000 years ago. It only reached Europe approximately 600 years ago, following the Columbian exchange. To name this new spiece the Spanish adopted the Taíno word mahis, which then spread to Italy and other parts of Europe. In Brazil, Portuguese did it too, with the Tupi term abati.

Across Europe, maize often received names that followed a common pattern: a generic cereal term combined with a foreign ethnonym. For example, Italian grano turco and German Türkischer Korn both mean “Turkish grain,” reflecting the crop’s route into Europe through the Ottoman Empire. In other regions, it was linked to another country: Turkish mısır and Armenian եգիպտացորեն (egiptacoren) refer to Egypt.

In many cases, maize was linguistically assimilated to Old World cereals. In Portuguese, milho originally referred to millet and comes from Latin milium. Similarly, in several Northern Italian dialects, the Latin word frumentum (meaning “grain”) was repurposed to refer to corn.

Perhaps the most intriguing and mysterious term is kukuruz, which spread widely across Eastern Europe with little variation in form or pronunciation. Its origin is uncertain. As far as we can know, the word appeared in Serbo-Croatian, but its deeper roots remain unclear. It may not be originally Slavic. Some theories suggest it derives from Ottoman Turkish قوقوروز (kukuruz), possibly borrowed from Albanian kokërrëz (a diminutive of grain or kernel) or from Proto-Slavic kurъ (“cock”).

Millet, the resilient

Like wheat, millet has a rich variety of etymological roots: In the West, terms derived from the Latin milium are predominant. In the North, the Germanic hirsijo is common—except in English, which also adopted the Latin term. In the East, there are two main Slavic roots: proso and, in some languages, pьšeno. Further east, the Turkic tarig appears. In the southeastern Mediterranean, the most common terms trace back to the Proto-Semitic root tahan.

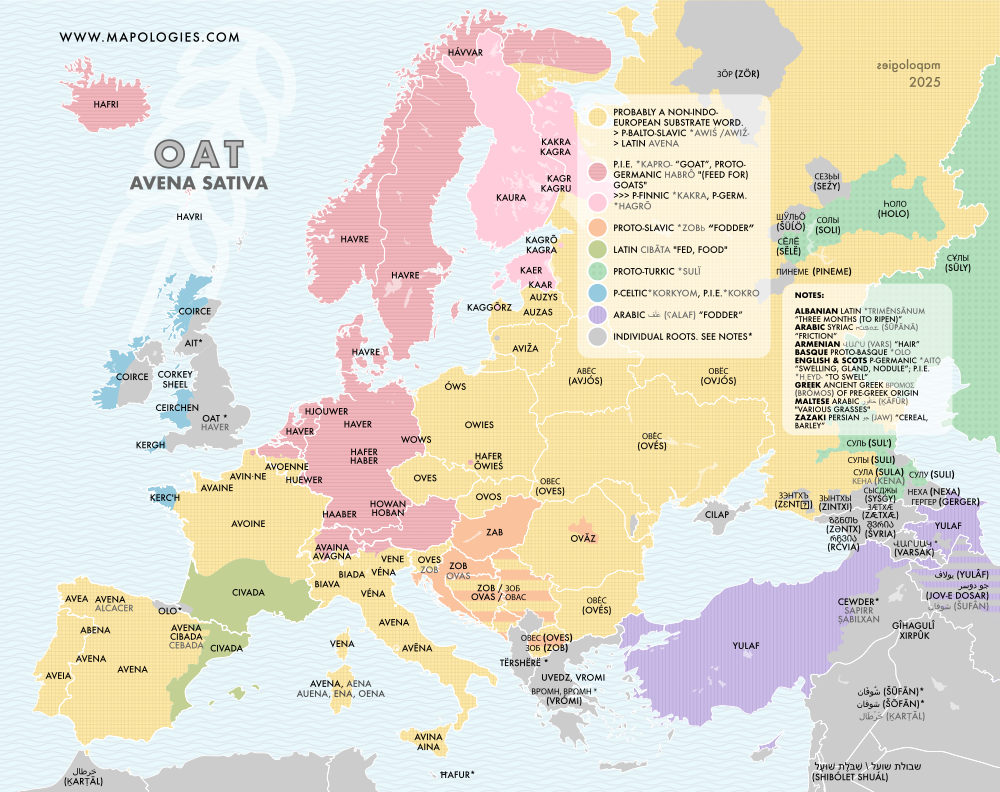

Oat, the porrige ingredient

Many Indo-European languages share the same root for oat: Portuguese avena, French avoine, Slovak ovos, and Russian овёс (ovyos). All of these forms descend from an ancient root that, interestingly, was probably of non–Indo-European origin.

Fodder

The Germanic languages, however, draw on the Proto-Indo-European root kapro, which also appears in English words such as the zodiac sign Capricorn and the adjective caprine—both related to goats, since the root was associated with fodder, particularly that used for feeding goats. Southwestern Romance languages also preserve a root meaning “fed, food” from Latin civada. Another noteworthy example comes from Proto-Slavic zobь “fodder”, which is reflected in several South Slavic languages as well as in Hungarian zab. Finally, Turkish and Azerbaijani yulaf were borrowed from Arabic عَلَف (ʿalaf) “fodder”.

Rice, the Chinese

Rice was first cultivated in the Far East as early as 10,000 years ago. From there, rice cultivation gradually spread westward. This movement is mirrored by the journey of the word for rice across languages. In English, the word rice comes from Old French ris, which was borrowed from Old Italian riso. That, in turn, derives from Byzantine Greek ὄρυζα (óruza).

Interestingly, not all languages followed this etymological path. Some languages — notably Turkish pirinç, and Georgian ბრინჯი (brinǯi) — derive their word for rice from a different Persian root. Despite these surface differences, both major linguistic branches ultimately stem from the same origin: Old Persian vrinjiš.

Yet not all terms for rice derive from Persian. In several Turkic languages, a completely different etymology is found, Proto-Turkic düg that means “to pound” — likely referring to pounded or husked grains rather than rice specifically.

Rye, the Northern European

As in previous cases, rye is a cereal whose name is widely spread across European languages. Most likely, it was a wanderwort borrowed into Proto-Indo-European as *Hrugʰís. From this root we get English rye, German Roggen, Lithuanian rugys, and even forms in non–Indo-European languages such as Hungarian rozs. Slavic languages also share this heritage, for instance Slovak raž, however, not all of them use this root: Czech žito and Belarusian жыта (žyta) instead continue Proto-Slavic žito.

Romance languages derived from Latin secale gave French seigle, and was even borrowed into Greek σικάλι (sikali). In the Iberian Peninsula, however, a different Latin root became dominant: centenum (“a hundred”), referring to rye’s reputation as a highly productive crop.

Further east, we encounter other interesting roots. In northeastern Asia, a Classical Persian word جو ـتر (jaw dar, “barley-like”) spread, reflecting rye’s role as a secondary crop, often growing as a mimic among wheat and barley fields. This may also explain why in some languages rye is described as “black wheat,” for example in Chechen ӏаьржа кӏа (ˀärža kʼa) and Kazakh қарабидай (qarabıday).

Wheat, the white

If you’ve ever confused “wheat” with “white,” or even if you haven’t but thought they seemed strangely similar, you’re not entirely wrong. The word “wheat” traces its origin back to the Proto-Germanic *hwītijaną, derived from *hwītaz, meaning “white.” This likely refers to the light color of wheat compared to other grains. This Germanic root is found in several Germanic languages (excluding Dutch) and was also adopted by their Lithuanian neighbors. The Latvian word is a cognate, that traces back to the Proto-Indo-European root *ḱweyt-, meaning “to shine.”

Another significant family of languages, the Turkic languages, carried the word boguday from the eastern steppes all the way to the west. As the Turkic-speaking peoples expanded their influence across vast territories, they brought not only their customs and traditions but also their language. This migration of language and culture is evident in the Hungarian word búza, which is derived from it.

From grain to flour

Slaves also share an ancient root for the word “wheat,” pьšenica, which originates from pьšeno, meaning “millet.” This term can be traced back to the Proto-Indo-European root peys, meaning “to grind,” a reference to the common practice of crushing cereal grains into flour. Similarly, the Celtic languages derive their word for wheat from a different process, winnowing, reflected in the term nixtos “winnowed.” If you look further south on the map, you’ll notice that the Latin term triticum, which is also the scientific name for wheat, comes from the verb terō, meaning “grazing or grinding.

In addition to triticum, there are three other Latin terms associated with wheat: frumentum, granum, and bladum, making the etymology map of wheat particularly intricate. The word frumentum also originates from a verb, fruor, meaning “to enjoy,” which is the same root that gave rise to the word “fruit.” Granum is straightforward to recognize, as it directly translates to “grain” and as we saw it is also connected to the concept of “corn.” Finally, bladum, over the centuries, it underwent significant semantic changes: it was borrowed from Frankish, originally referred to “field produce,” it stems from the Proto-Germanic blēduz, “flower, leaf, blossom.”