Day

The notion of a “day” may appear straightforward, yet its complexities emerge when considering diverse linguistic and cultural viewpoints. While commonly perceived as a 24-hour period, it can also denote the daylight segment. The word day follows the classical division according to language families: Germanic, Turkic, Slavic, and Semitic.

However, certain language families, like Romance and Celtic, have undergone division into two distinct branches. For instance, Spanish “día” and Romanian “zi” stem from the Latin “dies.” In contrast, French “jour” and Italian “giorno” are linked not to “dies” but to Latin “diurnum (tempus),” meaning “day (time)”. Surprisingly the adjective “diurnus” derived from the noun “dies”.

Despite contemporary linguistic disparities, some languages share ancient Indo-European roots. For instance, Greek “ἡμέρα” (imera) and Armenian “օր” (or) trace back to the Proto-Indo-European root *h₂eh₃em-, signifying “daylight” or “to shine.” Similarly, in Georgian, the term for “day” is “დღე” (dɣe), while in German, it’s “Tag,” both descendants of the root *dʰegʷʰ- or *dʰegʷʰos, connoting “to burn” or “daylight.”

Tomorrow

Days of the week

In ancient times, the days of the week were intricately linked with celestial bodies, each dedicated to celestial bodies believed to hold sway over earthly matters. This connection persists in English with names like Monday (Moon), Saturday (Saturn), and Sunday (Sun). In Romance languages, such as Italian, this association is even more evident. For instance, Lunedì, or “moon+day,” is followed by Martedì, meaning “Mars+day,” then Mercoledì “Mercury+day,” Giovedì “Jupiter+day,” and Venerdì “Venus+day”.

The other days of the week in English are linked to Norse mythology. Tuesday is associated with Tyr, Wednesday with Odin, Thursday with Thor, and Friday with Frigg. These deities correspond closely to the Roman days of the week, referred to as “interpretatio germanica.” In Latin, Tuesday is Dies Martis (Mars), Wednesday is Dies Mercurii (Mercury), Thursday is Dies Iovis (Zeus), and Friday is Dies Veneris (Venus). This connection persists in most Romance languages as well.

When we observe the names of the days of the week in various languages, we notice a common trend where they are often named after their position within the week. A prime example of this is the Lithuanian days of the week, it follows a sequential pattern starting with Monday: Pirmadienis (“First Day”), Antradienis (“Second Day”), Trečiadienis (“Third Day”), Ketvirtadienis (“Fourth Day”), Penktadienis (“Fifth Day”), Šeštadienis (“Sixth Day”), and Sekmadienis (“Seventh Day”), which corresponds to Sunday. However, it’s crucial to recognize that the choice of which day is the first day of the week isn’t universal; rather, it’s influenced by cultural factors.

This is a very general view of the days of the week in different languages. Now let’s see it in more detail.

Monday

The term “Monday” in English traces its roots back to Old English as “Monandæg,” which translates directly to “Moon‘s day.” This derivation is a borrowing from the Latin “Lunae dies.” Romance languages further evolved this term into modern equivalents such as “lunes,” “lundi,” “lunedí,” and “luni.” Many of the names for days of the week in English and other Germanic languages, like “Montag” or “Mandag,” were influenced by their Latin counterparts, a phenomenon known as “interpretation germanica.”

This is one way to name this day, predominant in the West, but there are two more:

The second way is the peculiar situation that, while Monday is considered for many of us the first day of the week, only a few languages (marked in green on the map) designate it as such: Lithuanian pirmadienis. In some other languages, it is viewed as the second day, as evidenced by terms like “segunda-feira” in Portuguese, Δευτέρα (Deftéra) in Greek, or الاثنين (al-ithnayn) in Arabic, as they count Monday as the second day from Saturday.

The third way is the most common in the East. A straightforward approach is to identify Monday as the day immediately following Sunday. In all Slavic languages, it can be translated as “After Sunday,” as well as in Turkish and Azerbaijani.

Tuesday

In English, the idiom “on the second Tuesday of the week” is used to convey that something will never happen. This idea stems from the fact that in countries like Canada and the USA, Tuesday is considered the third day of the week. However, this notion is not universal across languages.

Certain languages, identified by green colors, link the name Tuesday to the number three or third day of the week. In contrast, other languages, colored in yellow, associate the name with the number two, indicating it as the second day. This variation arises from the different interpretations of the week’s starting day; for instance, while some consider Sunday the last day, others designate Saturday as such, as discussed in the case of Monday.

War of words

It’s interesting to note that Western languages, such as English, don’t name days based on their position in the week. Instead, they often associate them with gods or celestial bodies. In Latin, for example, “Diēs Mārtis” or “Mārtis diēs” was associated with Mars, the God of war. Catalan “dimarts” came from the first combination, and Italian “martedì” from the second. Furthermore, German-speaking people later connected this association to their own gods. They honored Tyr by naming a day after him, Tīwas dag, which led to the English word “Tuesday.”

Wednesday

Wednesday, known as “Woden’s Day” in Old English, derives its name from the Norse god Odin, also known as Woden. In Latin-based languages, Wednesday is often linked with the planet Mercury, deriving from the Latin name for the day, “dies Mercurii.” This association extends to the Roman god Mercury, who shares attributes with Odin, such as being the messenger of the gods. Again an example of the conection of day and planets.

Middle day

As we venture eastward, the linguistic landscape undergoes significant changes. Among the languages highlighted in yellow, Wednesday holds a special significance as the “middle (of the week).” While Slavic languages typically designate days of the week with numbers, in this instance, they use terms signifying “middle,” as evidenced in Polish (Środa) and Bulgarian (Сряда). Also some non-Slavic languages, like German (Mittwoch) or Finnish (keskiviikko), convey the concept of “middle + week” in their respective names for Wednesday.

Indeed, certain languages attribute numerical meanings to the days of the week, but intriguingly, these meanings differ between regions, specifically South and North. For example in the South, in the Mediterranean, Greek (τετάρτη), Turkish (Çarşamba), and Hebrew (יום רביעי), Wednesday signifies the “fourth (day).” Conversely, in the northern Baltic states such as Estonian (kolmapäev), Latvian (trešdiena), and Lithuanian (trečiadienis), the terms denote the “third day” of the week.

Thursday

In Norse mythology, Thor is the god associated with storms, lightning, and thunder. Similarly, in Roman mythology, Jupiter assumed a comparable position as the god of the sky and thunder. Thursday was attributed to Jupiter, a tradition adopted by Germanic peoples as well. Additionally, ancient Albanians also adhered to this cultural practice of linking Thursday to the deity of fire.

Thursday, according to the ISO 8601 international standard, is officially acknowledged as the fourth day of the week. Interestingly, in many Central and Eastern European languages, the term for Thursday directly means “the fourth (day)”. However, in numerous other languages such as Portuguese, Greek, and Armenian, among others, Thursday is considered the fifth day of the week.

Friday

The fifth day

For most languages represented in the map, the first day of the week is Monday, and thus Friday is the fifth day: for example, in Russian (пятница, pyatnitsa) and Ukrainian (п’ятниця, pyatnytsya). However, Friday is referred to as the sixth day of the week in languages that start the week from Sunday: sexta-feira in Portuguese and Galician.

A day to fall in love

In most West European languages, the name for Friday derives from goddesses associated with love, beauty, and fertility: Venus and Frigg. The last is the Norse goddess of marriage and motherhood, in Germanic languages like Norwegian (fredag) and Danish (fredag). Venus, in Romance languages like French (vendredi), Italian (venerdì), and Spanish (viernes), was the Roman goddess and also the name of the second planet of the solar system.

Thank God it is Friday

Religious rituals have shaped the way people behave through the week, dividing them into regular and holy days. Many languages took the name from Arabic اَلْجُمْعَة (al-jumʕa) meaning that is the day to congregate or gather since Muslims hold every Friday the “Friday payer”. Other languages borrowed from Ancient Greek παρασκευή (paraskeuḗ) which means “preparation” before Sabbath. In the North Fridays are related to “fasting” because The Catholic Church historically observed this day as special.

See also Friday the 13th in different languages here or about the origin of Black Friday.

Saturday

Day of rest

Saturday holds a unique significance. By this, we don’t imply it solely as a day for leisure, laziness, or festivities, but rather in the etymological sense. Unlike the names of other weekdays, the majority of languages trace the origins of “Saturday” back to the Hebrew term שבת (Shabbat). Take, for instance, Portuguese (sábado), Hungarian (szombat), or Russian (суббота). Notice the striking similarities? Despite their diversity and dispersion across various regions, these languages echo the sounds of a shared ancestral root. From the team of mapologies, we propose to rename it as “Partuday”.

Saturn’s day

This linguistic pattern isn’t universal at all, particularly evident when observing regions to the north on the map. Now, consider English Saturday. Its linkage to Saturn, the celestial body (as well as the ancient Roman deity), is unmistakable. This connection is rooted in Latin, where both dies Sabbati and Saturni dies coexisted at different times.

The two Germanies

Germany is divided still by an unseen linguistic barrier: While Saturday is recognized as Samstag (Sabbath day) in the majority of the country (also Switzerland & Austria), in the Eastern and some northern regions, it is Sonnabend. This latter term means “sun(day) eve(ning),” hence, translating to “The day before Sunday.” In contrast, for Turks, it is “After Friday.” Baltic languages, on the other hand, take a straightforward approach and designate it as the “sixth day.”

Bath day

Languages derived from Old Norse, including Finnish and Estonian which adopted it later, incorporated the term laugr or laug, meaning “bath.” This practice originated from the Viking tradition of bathing on Saturdays. Do you have a hot bath too every Saturday evening?

Sunday

Keep it holy

Sunday, renowned for its association with worship across many cultures and its link to religious observances or holidays (as seen in Estonian and Latvian), is commonly regarded as a day of rest. Except for Russian, all Slavic languages utilize a word stemming from Proto-Slavic *neděľa, meaning “no work.”

Furthermore, the tradition of markets being closed on Sundays is a prevalent cultural practice in many regions, influenced by religious customs and societal norms prioritizing rest and communal activities over commercial endeavors. However, this is not the case in Islamic cultures. Interestingly, while Turkish uses “bazar” (market), so does Hungarian. Surprise!

Nothing new under the sun

In ancient cultures, Sunday was already connected to the top deity, represented as the Sun. Greeks referred to it as ἡλίου ἡμέρα (hēlíou hēméra), while the Romans called it dīes sōlis. This connection is still present, in English, Sunday’s name originates from Proto-West Germanic *sunnōn dag, translating to “day of the sun,” a calque of the precedent names. We find this root in other Germanic languages: German “Sonntag” and Dutch “zondag”.

Later, under the influence of early Christian beliefs, Sunday became linked to God as “Our Lord.” In Romance languages such as Spanish “domingo”, French “dimanche”, and Italian “domenica”, the names allude to the Latin phrase Dies Dominicus “day of the Lord.”

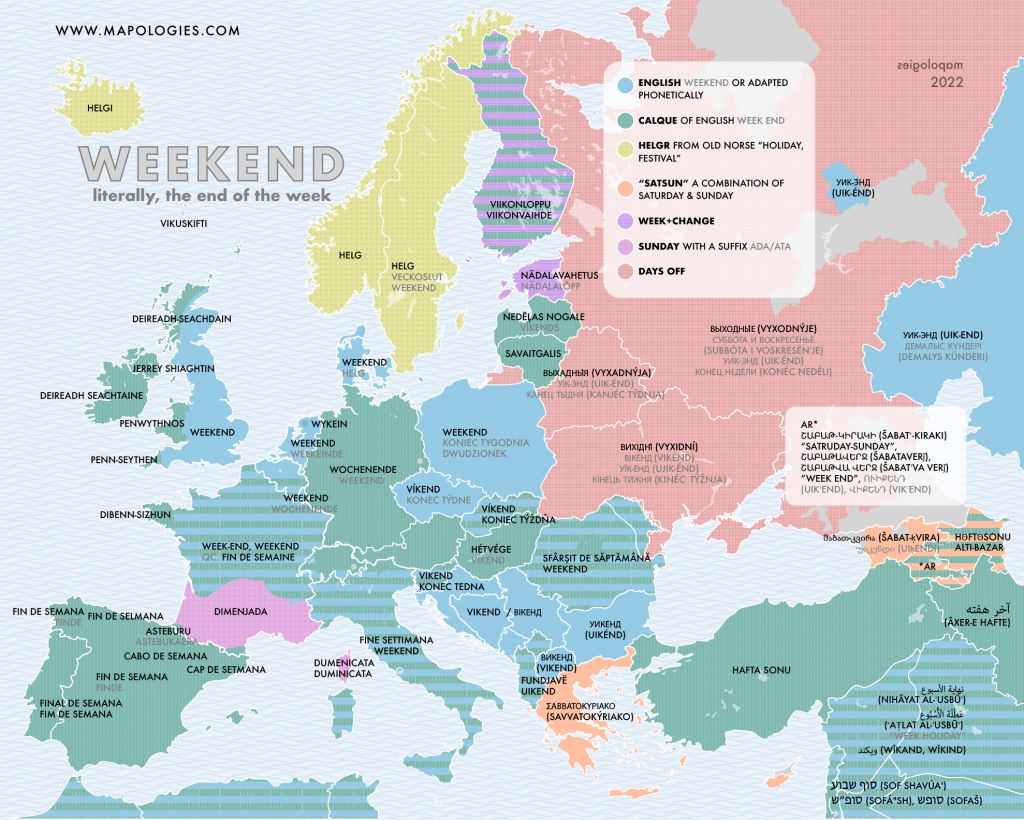

Weekend

The concept of the weekend historically centered around Sunday as a day of rest and holiness, marking the end of the week and completing the weekly cycle, particularly significant in Christianity. However, its universality is challenged by the observance of the Shabbat by Jewish workers on Saturday, their most sacred time. The idea of a two-day weekend, including Saturday and Sunday, was first documented in 1908 in a New England mill. However, it wasn’t until 1932 that the United States officially adopted the five-day workweek system in response to the unemployment crisis of the Great Depression.

Seasons

Spring

Spring is found in more than fifteen languages on this linguistic map, each with a unique etymological origin. English, among them, employs “spring” to denote the season when vegetation begins to “spring” forth, or emerge. Before its adoption in English, the word was “Lent”, like in Dutch Lente, from Proto-West Germanic *langatīn, literally “longer day” in reference to the lengthening of daylight.

Many other languages share a common ancestor despite formal differences. Surprisingly, words like Portuguese “primavera,” Icelandic “vor,” Ukrainian весна́ (vesná), or Zazaki “wesar” all share a common origin: the Proto-Indo-European word ” *wósr̥ for spring, from which their respective offsprings spread across regions.

Summer

Languages that are typically distinct find a common link in summer. While Romance and Baltic languages often differ, they share the Proto-Indo-European root *wósr̥, meaning “spring” and originally “becoming warmer.” For example, the Portuguese “verão” and Latvian “vasara” derive from this root. Similarly, the German “Sommer” and Kurdish “havîn,” despite their different appearances, both stem from the Proto-Indo-European root *semh₂-, meaning “summer” or “half of the year.”

Autumn or fall

A trio words

This season can be called autumn, fall or harverst. The first is connected to other Romance languages: Italian “autunno,” French “automne,” and Spanish “otoño.” These words all trace back to the Latin “auctumnus.” In North America, the season is commonly referred to as “fall,” a term that obviously comes from the phrase “fall of the leaf.” Another, more dialectal way to refer to this season is “harvest,” which links to other Germanic languages: Dutch: herfst, German: Herbst or Icelandic: haust. They originated from the Proto-Germanic *harbistaz, where it initially referred to both the harvest season and autumn.

Between summer and winter

The Old Proto-Slavic (j)esenь gave rise to many descendants, such as modern Ukrainian о́сінь (ósinʹ), modern Bulgarian е́сен (ésen), and Old Czech jeseň. Nowadays in Czech, however, the word podzim is used more often, which literally means “under winter.” This construction, where autumn is described as the season preceding winter, can also be found in a neighboring language, Sorbian (nazyma) and more distant one, Irish (fómhar). Just the opposite of Basque udazken (uda+ azken, “summer + last”).

Winter