A fruit is the mature ovary of a flowering plant and plays a crucial role in spreading the plant’s seeds. It forms after the flower is fertilized. In this post, we will explore the origins of terms related to fleshy fruits that have a soft, edible part. Berries have a separate post here. The term fruit also includes nuts (which are hard-shelled seeds), and grains (the seeds of cereal plants).

Melons and apples of discord

This is like comparing apples and oranges! Notice that in Italian is quite obvious that mela (apples) and melone (melon) are closed related etymologically. The Greek word μῆλον (mâlon) generally meant fruit but particularly was used for apples. Thus it is still present in some fruit’s names: For example, Spanish melocotón “peach” (see below).

Just above this text we are showing the map of Cucumis melo (known as melon) from Greek Μῆλον ´Πεπων (Melon Pepon). Most languages retain the first part, but some language in the Balkan peninsula took the second.

Some Slavic languages and Hungarian, however, use a totally different Greek root: Κυδωνιον Μῆλον (Kudṓnion Mêlon). It means “Cydonian apple”, which evolved in English (and other languages) into “quince” (see bellow). This is as messy and it sounds.

Turkic languages share their own root. Not Greek at all, coming as far away as from the Himalayas: It is possible that comes from Tibetan ག་གོན (ga gon) a word for melon and gourd.

Apricots, plums, and peaches can be disconcerting

What a big mess!

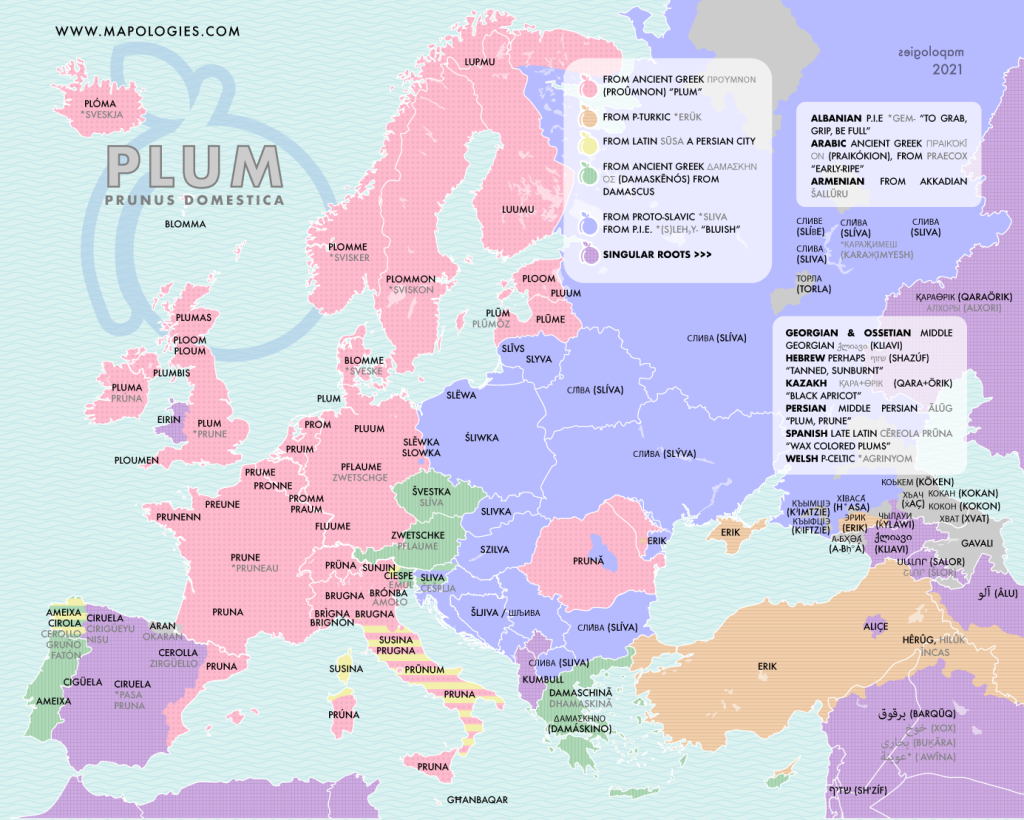

Plums, peaches, and apricots belong to the same family, genus Prunus. It is not surprising since they are very similar. More surprising is that cherries, nectarines, and almonds also belong to this group. However, the most surprising fact is that their etymologies are entangled. Most languages derived the word apricot from Arabic al-barquq, which literally translates as “the-plum”. The word was taken from Byzantine Greek berikokkia which is probably from Latin (mālum) praecoquum “early-ripening (apple, fruit)”. The reason is the apricots ripen earlier in summer.

Its scientific name, Prunus armeniaca, reminds us that for many centuries it was believed to be from Armenia. It was cultivated there from Ancient times, but now we know that the domestication happened somewhere in Central Asia. Later Alexander the Great introduced them to Europe.

Another confusing etymology is that both fruits are supposed to be from Damascus. Unlike other Slavic languages, that use a word derived from Sliva for plums (Prunus domestica), Czechs use švestka, an adaptation of the German word Zwetschge, a type of plum, which originated from Latin damascēna and from Ancient Greek δαμασκηνά (damaskēná) “damascene plums”. Modern Greek δαμάσκηνο (damáskino). But in Portuguese and Spanish Damascos are apricots! It is simply shocking to discover that plums in Portuguese and Galician are etymologically related to Czech and Greek: Latin damascēna (prūna) > Vulgar Latin damascina > Old Portuguese dameja > Modern Portuguese ameixa.

It also happens in Turkic languages: ərik is an apricot in Azerbaijani (and similarly in Kazakh, Tatar, and Bashkir). But erik is plum in Turkish.

Is it really Persian?

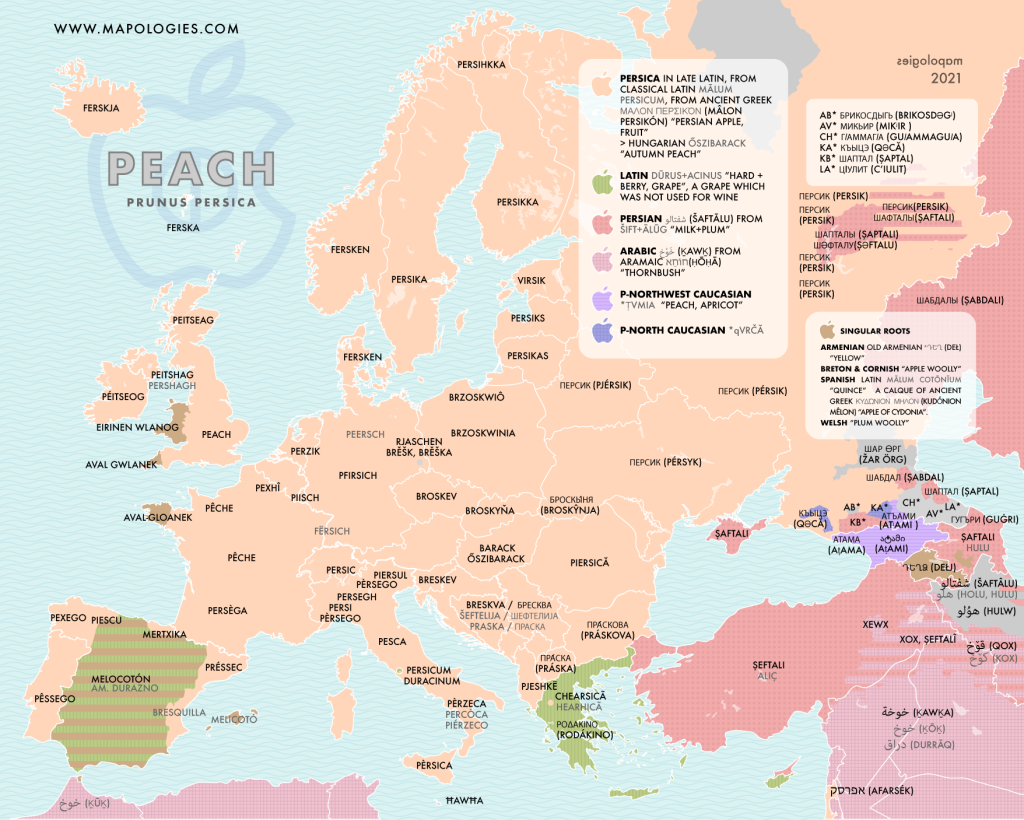

Peach has a quite homogenous etymological map. Only a few languages adopted a term that does not come from Latin Persica (Persian). Like many other fruits, even if the Romans believed it was from what is nowadays Iran, the truth is that it comes from China. Slavic languages borrowed the word through a series of deep transformations. So Polish brzoskwinia, despite seeming to be very different, it comes from the same root. The same happens to Hungarian barack.

American Spanish and Greek share another Latin root: dūrusacinus, meaning “hard berry or grape”. Most Turkic languages borrowed from Persian šaftālu which originally meant “milk plum”. Kurdish uses this term along with the Arabic one, Kawka, which in ancient times might have meant “Thornbush”. Another metaphor is present in some Celtic languages where they called something like the “woolly fruit” (either plum o apple, depending on the specific language, check the legend). Finally, in Spanish from Spain, we can find the term melocotón, whose etymological root will appear again in this post, since it comes from the Latin malum cotonium, the name that received quince. The name comes from Kydonia, a city in Crete. However, it might appear to be from “cotton”, although this might be a folk etymology. In the Spanish Wikipedia, we can read:

“Prunus persica, originalmente Amygdalus persica L., melocotonero (del latín malus cotonus, «manzana algodonosa» —en alusión a la piel del fruto—)”

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prunus_persica

Quince

Cherry

Although the word cherry is often used as a single term, it actually refers to two distinct species of fruit trees: Prunus avium (sweet cherry) and Prunus cerasus (sour cherry). Similarly, in German, we find Süßkirsche for sweet cherries and Sauerkirsche for sour cherries; or in Italian, the terms ciliegia dolce and ciliegia acida (or amarena).

The etymological root of the word “cherry” are ancient and widespread across Europe, largely due to the influence of Vulgar Latin ceresia, derived from Late Latin ceresium or cerasium. These, in turn, were borrowed from Ancient Greek κεράσιον (kerásion) and κερασός (kerasós), both meaning cherry. The ultimate origin of the word is believed to trace back even further, possibly to a pre-Greek or Anatolian source.

Mistletoe

While some languages use compound forms to distinguish between the two, many others use entirely different roots: In Spanish (along with the other languages of the Iberian peninsula), Prunus avium (sweet cherry) is called cereza, whereas Prunus cerasus (sour cherry) is commonly referred to as guinda. The second root might be the descendant of Proto-Germanic *wīhsilō, from Proto-Indo-European *weyḱs- “mistletoe”.

In Polish, the word czereśnia refers to the sweet one, while wiśnia is used for the sour one. The term can be traced back to Proto-Slavic višьňa, which itself is believed to be cognate with Proto-Germanic wīhsilō. Interestingly, the root wiśnia is not only widespread among Slavic languages, but also in several other linguistic families, including Greek, Turkish, and Lithuanian.

The Mediterranean Triad

The Mediterranean basin, where important civilizations began, has given us a unique legacy called the Triad: grapes, olives, and grains. These three elements represent the heart of the region’s abundant agricultural history, as well as its religious and culinary traditions. They serve as the basic ingredients for producing three essential food products: wine, oil, and bread.

Grape

In Latin, “uva” evolved from the Proto-Indo-European root *h₁eyHw- meaning yew, willow, and grapes or vine. As the Roman Empire expanded its influence, Latin terminologies related to viticulture and winemaking spread across Europe. The Latin word “uva” remained the same for millennia, in Italian, Portuguese & Spanish, but in other Romance languages was different: For example, in French “raisin” or Catalan “raïm” comes from Latin racēmus “bunch of grapes“

Similarly the English word “grape” ultimately finds its origins in Old French “grape” or “grappe,” which means a cluster of fruit or flowers, particularly a bunch of grapes. The word itself comes from the verb “graper” or “caper,” meaning “to pick grapes,” from Frankish word *krappō, which means “hook.” Another example is the words derived from Proto-Slavic grozdъ “cluster, bunch”.

The association between grapes and wine was so strong that it extended beyond the borders of the empire, leading to the incorporation of the Latin word vinum meaning “wine,” into the vocabulary of Germanic and Slavic languages. Notable examples include Icelandic (vínber), Polish (winogrono) and Russian (vinograd, виноград).

Olive

Fig

The tripoint near the village of Beregsurány in Hungary, Bercu in Romania, and Dyida (Ukrainian: Дийда) in Ukraine is not only a geographical curiosity but also an etymological one.

On the Hungarian side, the word for “fig” — “füge” — is quite familiar even to English speakers, who might recognize it. This resemblance is no coincidence: füge is a direct descendant of the Latin word ficus. Many European languages share this Latin heritage, although with some unusual spellings, such as Spanish higo or Finnish viikuna.

In contrast, just across the border in Romania, the word for fig is smochină. This term traces back to the Slavic root смокꙑ (smoky), from Proto-Slavic smoky, a word of uncertain origin, but possibly connected to the Gothic smakka.

Meanwhile, in Ukraine, the situation is even more diverse. Ukrainians might use the Slavic term смо́ква (smókva) for “fig”. However, another common word is інжир (inzhyr), which has a very different origin. Inzhyr came into Ukrainian through Turkish (incir), itself borrowed from Persian انجیر (anjir, meaning “fig”).

Aubergine or eggplant

Why do some English speakers say “aubergine,” while in America, “eggplant” is more common?

Aubergine is also used in French and German. Other languages have different names, like Spanish “berenjena” or Catalan “albergínia.” Despite these differences, etymology often reveals a common origin: Sanskrit word वातिगगम (vātigagama), literally “the plant that cures the wind. Some words are very similar to the original like Persian word بَادِنْگَان (bādingān)or Turkish “patlican.” Some other variations are unexpected. For example, the Italian “melanzana” added “mela” (apple) to the Arabic “bāḏinjān.”

Egg-shaped

It may also be surprising that some languages, particularly Nordic ones, use “eggplant.” For example, Norwegian “eggfrukt” (egg-fruit). While we often picture a purple aubergine, some varieties are white, and when they begin to grow, they actually resemble a small white egg.

The citrics

Lemon

Lemons appeared for the first time in northeast India. The name is originally Sanskrit, Nimbu, which means lemon and lime. We can not know for sure. Then it reached Europe thanks to Persians, Ottomans, and especially Arabs. According to some sources as early as the 2nd century. However, the original term might have come from even further, from nowadays Malaysia. Genetic studies support this theory.

In the center and north of Europe, another root exists, like in Latin citrus. It comes from Ancient Greek for cedar: kedros. Apparently, in Athens, the smell of citric and thujas was similar. The ultimate origin is completely unknown, but some suspect it might be some kind of borrowing from a Semitic language.

As we mentioned above the Romans called them citron and later it became the scientific term for a genus (citrus), an acid (citric), a grass (citronella), or a mineral (citrine).

New world

Courgette or zucchini

A “small marrow”, scientifically known as Cucurbita pepo, is descended from squashes first domesticated in Mesoamerica over 7,000 years ago. There are three words in English: courgette, zucchini, and baby marrow. Does it sound different? First two share the same origin. The word courgette was borrowed from French, while zucchini comes from the Italian plural nouns zucchino or zucchina. Interestingly, both terms descend from the Latin cucurbita, meaning “gourd.” French influence spread the term courgette across Western Europe (Portuguese curgete or Irish cuiséad), whereas the Italian zucchini became more popular in Central Europe (Hungarian cukkinni or Czech cuketa). In Eastern Europe, the most common root is the Turkish word kabak, a diminutive of *kab “cover, container”

In many languages, the vegetable is referred to as a “small pumpkin.” For example, Spanish uses calabaza and calabacín, Serbian uses tikva / Тиква and tikvica / Тиквица, and Armenian uses դդում (ddum) and դդմիկ (ddmik).

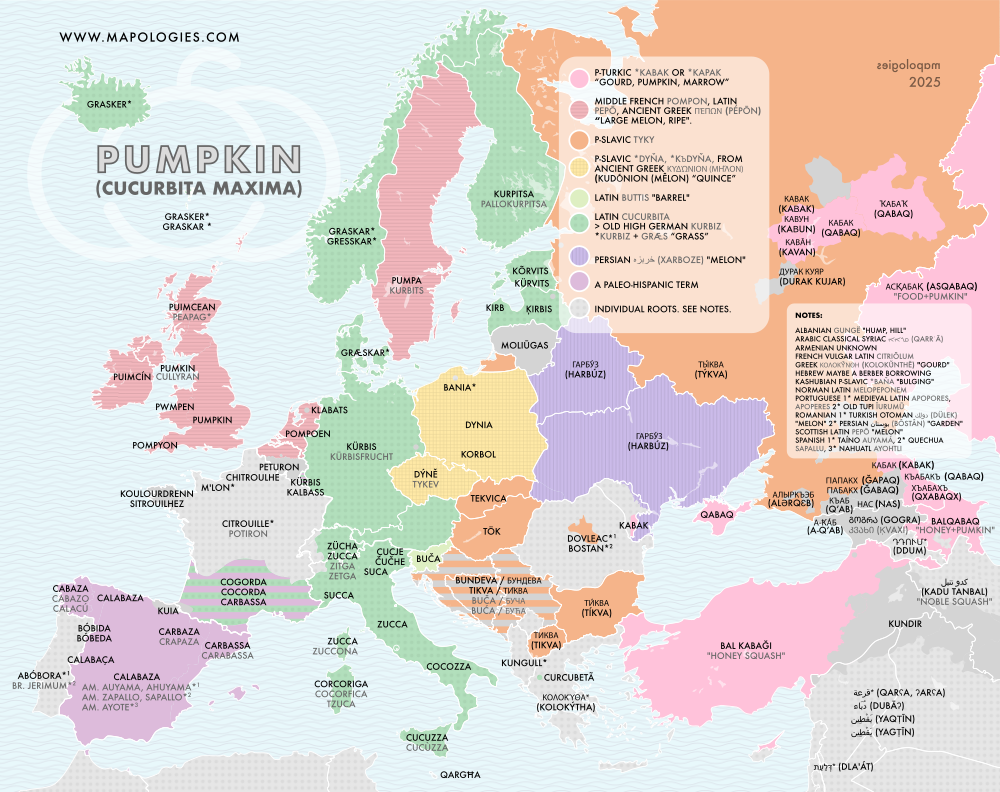

Pumpkin

There is not any vegetable more connected to Halloween than pumpkin. The Englsh word, like Dutch pompoen and Swedish pumpa all belong to the Germanic language family. Despite this, it is not a Germanic word, it originates from French pompon and Latin pepo, which in turn were borrowed from the Greek pepon (πέπων), meaning “ripe.” This shared etymology connects the word pumpkin to terms for “melon” in several Balkan languages: Bulgarian пъпеш (păpeš) or Romanian pepene.

Similarly, many modern words for these fruits in other languages derive from the Latin cucurbita — the scientific name — which also gave rise to English and French courgette.

This confusion between the names of different fruits is not unique. In the Slavic languages, for example, the Czech (dýně) and Polish (dynia) terms for “pumpkin” resemble, again, words for “melon” but in this case, in Russian (дыня, dynya) and Serbian (диња, dinja). At the same time, they are also etymologically connected to words like English quince, and are very close formally to Bulgarian (дюля, djulya) and Serbian (дуња, dunja). This is because all these ultimately go back to the Ancient Greek Κυδωνίον μῆλον (Kudṓnion mêlon), meaning “Cydonian apple.”

Sweet pepper

Caspicum annum is the scientific name of “sweet pepper“, which derived from Latin piper and Greek peperi, likely from Sanskrit pippalī. It first referred to black pepper, but after chili peppers were brought from the New World, the name was extended due to their similar spiciness. Several languages use also this root: French poivron, Italian peperone or Turkish biber share the same origin.

The powdered spice Paprika entered English from Hungarian, where it means both the spice and the pepper. Other Central European languages and Northern languages also have a single word. However, Paprika is not a native Hungarian word, it was borrowed from Serbian papar, meaning “pepper,” which is also coming from Latin piper.

Pimiento, on the other hand, comes from Spanish but it is not related to the previous ones, it traces back to Latin pigmentum “coloring” due to its bright color.

Pineapple

Pineapple, exemplifies how a word from the New World has successfully spread across many languages and cultures. The term “ananas” originates from Tupi, an Indigenous language of Brazil. Today, the word ananas is widely recognized across most of Europe. However, in some languages (Portuguese, English, Spanish, and Armenian) alternative names exist.

Interestingly, Brazilian Portuguese diverges from the widespread term ananas and uses “abacaxi”, a word also of Indigenous origin, but from an unknown root.

In English, ananas is not as common as “pineapple”. A compound word that combines “pine” and “apple”. Early European explorers thought the fruit resembled a pinecone, hence the name. Similarly, in Spanish, the word “piña” also means pinecone.

In Armenian “արքայախնձոր” (arkhaya-khndzor) translates to “king fruit.” This evocative name reflects the fruit’s regal appearance, as its leafy top resembles a royal crown. Interestingly, the scientific name Ananas comosus also alludes to this feature—“comosus”, meaning “tufted”, refers to the crown-like cluster of leaves atop the plant.

Starting in the 15th century, numerous vegetables, fruits, and animals were introduced to the Old World from the Americas and vice versa, a process known as the Columbian Exchange. Some examples include fruits like avocado, pineapple, papaya, and cranberry; vegetables like tomato, chili pepper, potato, squashes, and pumpkin; legumes like beans; cereals like maize (corn); or nuts like sunflower and peanut. In some cases, native words crossed the ocean along with them.

Sunflower

The modern scientific name for the sunflower, Helianthus, was coined by Swedish botanist Carl von Linnaeus, drawing from the Ancient Greek words ἥλιος (hḗlios), meaning “sun,” and ἄνθος (ánthos), meaning “flower.” This construction is found in several modern languages, such as English (sunflower), German (Sonnenblume), and Romanian (floarea-soarelui). Interestingly, Linnaeus’s own native language, Swedish, uses a more poetic term: solros, which translates as “sunrose.”

In many languages, the name of the sunflower highlights its heliotropic behavior, its tendency to follow the sun throughout the day. For instance, in Portuguese, girassol, in Hungarian, napraforgó, and in Arabic, زَهْرَة اَلشَّمْس (zahrat aš-šams). In other cases, such as Bulgarian слънчоглед (slǎnčogled), literally means “sun-gazer”.

In general, across a wide range of languages, the sunflower is consistently associated with the sun. In Polish, the flower is called słonecznik, and in Russian, подсолнух (podsolnukh) “under the sun”. A notable exception is found in Turkish, where the sunflower is known as ayçiçeği, literally translating to “moon flower.” This lunar twist makes Turkish a linguistic outlier in a global pattern dominated by solar imagery.

Tomato

Aztecs, Spaniards & Italians

Wild tomatoes (Solanum pimpinellifolium) are native to western South America. However, the domesticated tomatoes we use today originated with the Aztecs in Mesoamerica. The Spanish were the first to introduce small yellow tomatoes to Europe. What should this new fruit be called? Most languages, including Spanish, adopted the Aztec word from Nahuatl, tomatl, meaning “the swelling fruit.”

The Italians had a different idea. Pietro Andrea Mattioli initially suggested that this new fruit was a type of eggplant. In some languages, tomatoes—especially those with a purplish hue—are still associated with aubergines. Later, Mattioli proposed a different nickname: pomi d’oro, or “golden apples.” You can see on the map it is very popular label.

Love & Hate

Today, tomatoes are one of the most popular vegetables, in some languages they are even called “love apples” (a term that was once used in English). In many Central European languages, the word for tomato is derived from or a calque of the German Paradiesapfel, meaning “Paradise apple.”

However, tomatoes were not always so well-regarded. Names like “wolf-apples” in English or the scientific Latin name lycopersicum (which means “wolf-peach“), remind us that tomatoes were once considered toxic.

Can they make this map a little bigger? I don’t like having to squint.

Now it should be ok 😉

Sorry but your Melon map contains two huge mistakes.the Frenchman for Melon is not Abricot, and the Swiss is not Abricosa.

Thanks for the correction. We have just fixed this map.